Ancient South Arabia

The location, brief overview on kingdoms and timeline

By Ancient South Arabia, we refer to the historical region that corresponds to much of the territory of now days Republic of Yemen, known in the classical works as Arabia Felix (Fortunate Arabia). The land from which the Biblical figure Queen of Sheba have come, despite that no reference to this legendary queen has been found in the inscriptions so far.

Immigrants coming probably from the north-eastern Arabia, brought with them the rudiments of what was to become the highly developed civilization of Southern Arabia[1]. The beginning of the first millennium BC has witnessed a civil revolution in the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula, where an organized societies have developed as kingdoms. Sheba (or rather Saba), with its capital, Mārib, is now known from hundreds of inscriptions, as a the most prominent kingdom among the ancient south Arabian kingdoms.

Mārib is best known by its famous dam, which used to irrigate between 9 and 10 thousand hectares, it was 650 meters long and 15 meters high. The inscriptions mention that four restorations were made in this dam, between the middle of the fourth century AD to 558 AD; the dam finally collapsed in about 558 AD. and described in the Quran, and Islamic sources, as a historical turning point, explaining the migrations of tribes around Arabia.

The Great Dam of Mārib

Mārib is one of the largest archaeological sites in Arabia, it contains the economic, social, and political institutions, and thus form the focal point of the Sabaean kingdom. The inscriptions scattered throughout Awam temple, in Mārib, can be consider as an historical archive that covers long historical stages of this kingdom, and with its significant importance, "the Awam temple played the role of the Ka'ba in Mecca" according to Dr. Maraqten.

Islamic sources refer to ancient south Arabia by its last kingdom "Ḥimyar", although Quran itself devotes a whole chapter for Saba and its dam and "the two heavens"; lately these two heavens could be located and also recognized by names: Abyan and Yasrān. Sabā was the prominent Kingdome, alongside with: Maʿīn, Qatabān, Hadhramaut, Awsān, and Ḥimyar, which their history is marked with constant strife and wars. The few studies that have been done on the prehistory of the south Arabia indicate the significant human presence, as we find rock drawings done by hunters and herders, between the fifth and second millennia, although remain largely unresearched.

Scholars divide the history of South Arabia into two parts, although these periods may intersect: the first is from the eighth century BC until the first century BC, during this period, the caravan economy flourished. Oriented to the large markets of the Middle East, first around the Euphrates (8th and 7th centuries), then in Gaza (Persian period), and finally in Petra (Hellenic period), The Kingdom of Hadhramaut had strong trade relations with the Kingdom of Maʿīn, and flourished between the fourth and first centuries BC. As of the first century AD, the centers of power gradually shifted to the highlands (Sana’a, Dhofar, etc.) as well to coastal cities (Aden, Mocha, Mūzaʿ, Bir Ali, etc.).[2] The oldest evidence of the Qataban Kingdom dates back to 9th century B.C, while its end was in the second century, when it was annexed to the Kingdom of Hadhramaut around the third quarter of the second century AD[3]. This period ended with Rome's occupation of Syria (63 BC) and then Egypt (30 BC), and during this period, the famous failed campaign of Aelius Gallus took place to occupy the Arabian Peninsula, where he was forced to withdraw after a week (25-26 BC). Unfortunately, available ancient inscription didn't mention Aelius Gallus expedition, probably due to the lack of the sufficient excavation work in Yemen.

As for the second period, it starts from the first century to the third century AD, when the tribes of the mountains replaced those of the oases, here the Ḥimyar ites (their kings adopted the title "King of Saba and Dhū-Raydān") flourished for a century, with their capital was the city of Dhofar; and this historical period is better documented thanks to the large number of dated inscriptions that survived from this period[4].

Religion

According to the inscriptions and based on archaeological data, South Arabian paganism was astral foundation, worshiping the moon, sun, and perhaps some astral objects, traditionally recognized as Venus. The South-Arabian pantheon is not properly known, and the sex of some deities is still mysterious, However, the supreme male god was ʿAthtar, the god of irrigation through thunderstorms, worshiped all over south Arabia, alongside with national deities, such as Almaqah in the temple of the federation of the Sabaean tribes in Mārib; Wadd (meaning "love") in the kingdom of Maʿīn; ʿAmm (meaning "paternal uncle") in Qatabān; and Sīn or Syān in Hadhramaut; and several local deities, as several tribal groups had their own divine. No mythological texts have been discovered yet, although scholars have no doubt on the existence of mythological beliefs, orally at least, and thus not transmitted to us.

The divine played a huge role in the public and private life, and the state expressed itself through "national god, sovereign, people". The sovereign calls himself the "first-born" of the national god, and the nation is the god's issue (walad). [5]Personal names usually compound of gods' name. Sacred spheres and temples were subject to several restrictions, such as ritual purity. Votive texts reflected cases of violation of this sanctity and the penalties that resulted from that.

Deities were invoked usually for protection of the individuals and offspring, and against the enemas and misfortune; they were represented by their symbol-animal, such as bull, snake, eagle, gazelle, ibex, etc., or more frequently by an abstract symbol: bludgeon, door-flap, thunderbolt, etc.[6] The common magical formula in the Ancient South Arabian inscriptions "Wadd-ʾab", translated as (Wadd is father), usually appears on the amulets and buildings and private property. Beeston argues that the king of Awsan "Yaṣduqʾil", whom he dates to the late first century B.C. actually undertook two military campaigns to ensure that lucrative trade with the Mediterranean continued, he even dressed in Hellenistic costume, and consider by Avanzini as "a potentially interesting personality in Arabian history".

FPhoto after JEMEN, p. 309

Rituals varied between sacrifice, libation, burned offers, ritual banquets, and some more complex procedures such as the ritual hunt (aimed at the game consecrated to various gods), rogation for rain (rainmaking after a persistent drought), and dream incubation, (sleeping in a sacred place aiming for a specific dream to solve a problem).Pilgrimage, also, was an essential component of the ancient religion. The most important pilgrimage was undertaken for the Sabaean God Almaqah, in a procession to Awām, both men and women, as well as to local deities, like Qaynān and Du-Samāwi, and the Ḥadhramī God Siyān, and the Maʿīn God ʿAthtar. pilgrimage included ritual purity, processions, prayers, and other activities. It was during a specific Sacred Time and sometime on behalf of the deity order[7].

During the second half of the 4th century, monotheism has become an official religion, and pagan formulas disappeared from the texts, with rare exceptions. Formulas are invoking the "Lord of Heaven" and "the Merciful" (Rahmānān); Also, Christianity and Judaism, using the same terminology, has supplanted paganism. [8] Procopius mentioned "the old faith" of South Arabians which men of his day call "Hellenic". According to the Arab tradition, the Jewish faith was introduced to south Arabia during the reign of king Abūkarib Asʿad (around 430-450). Later, Christian trinitary formulas can be found for the first time in the inscriptions. Mummies also found in Yemen (in Shibam al-Gharas), which may reflect the believe in Afterlife.

Agriculture and economy

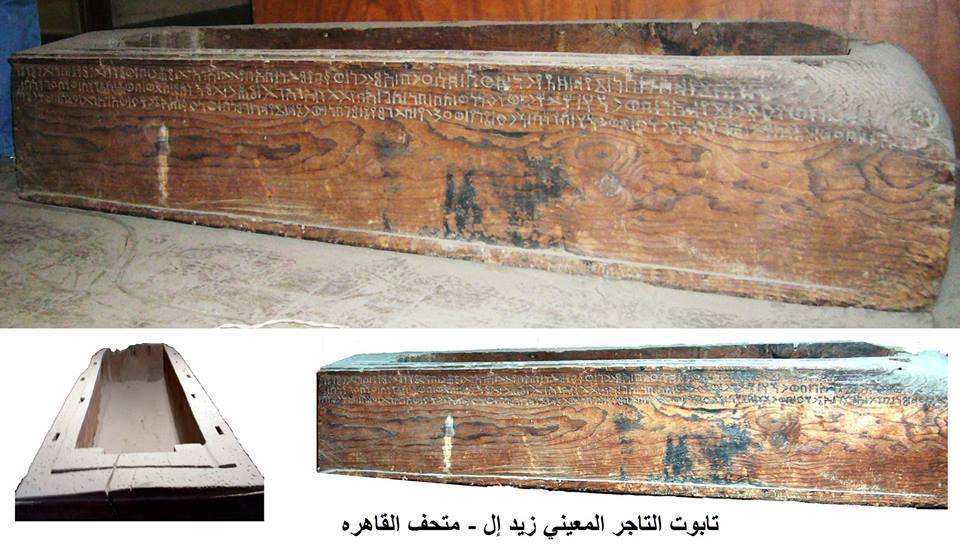

The economy of South Arabia was based on agriculture and trading of frankincense and myrrh, with distant nations. The first report of frankincense route is probably in the Old Testament (I. Kings 10) which tells of the visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (10th century B.C.), which suggests an established trade relation[9]. An Assyrian clay tablet refer to the Sabean king, Karibilu (=Karib Il), who sent gifts to the Assyrian king, around 685 B.C. Archologies found a tomb for a south Arabian merchant in Giza, Egypt dates back to around 264 BC, for a man named "Zayd El Zayd" who was importing perfume for Egyptian temples; they also found an inscribed artifacts in the Greek island of Delos, one of them is a cylindrical altar belongs to two merchants from Maʿīn in honor of their god Wadd, and dates back to the second half of the second century BC.

The economy of South Arabia was based on agriculture and trading of frankincense and myrrh, with distant nations. The first report of frankincense route is probably in the Old Testament (I. Kings 10) which tells of the visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (10th century B.C.), which suggests an established trade relation[9]. An Assyrian clay tablet refer to the Sabean king, Karibilu (=Karib Il), who sent gifts to the Assyrian king, around 685 B.C. Archologies found a tomb for a south Arabian merchant in Giza, Egypt dates back to around 264 BC, for a man named "Zayd El Zayd" who was importing perfume for Egyptian temples; they also found an inscribed artifacts in the Greek island of Delos, one of them is a cylindrical altar belongs to two merchants from Maʿīn in honor of their god Wadd, and dates back to the second half of the second century BC.

In Mārib, every spring and summer the valley is filled with biannual rain that falls on the mountains, and because of the low slope here, it is easy to cut irrigation channels, and finally, the relatively flat land becomes agricultural fields, which goes back to the late third millennium B.C.

The Qatabanian obelisk of Shamar (RES 4337A)

As for the Qatabanis, they were distinguished by extensive agricultural activity. They established irrigation projects in the valleys, built long canals, dug wells and built dams, they also enacted laws regulating their economic affairs. The kingdom of Maʿīn appeared on the scene in the fifth century BC, After Al-Jawf took control of the frankincense route; The Maʿīnians were mentioned by the classical sources, such as Pliny. They had several transit settlements, like as MSRM, in today Al-'Ula in north-western Saudi Arabia, Qaryat al Faw, and Dadan. This trade route extended mainly from the port of Qana to Gaza in Palestine, passing through the city of Shabwa and Mārib, and then passed through Wadi Al-Jawf, and from there to Najran, where it divided into two: The first pass through “Qaryat al Faw” in Wadi Al-Dawasir, and from there to “Hajar” in the Gulf region, and then to the south of Mesopotamia. The second extends from Najran towards the north, passing through Yathrib, then Dadan in the northern Hijaz and from there to Petra (Petra is attested in an Qatabanic inscription as "rqmm"). The road leads from Petra towards Gaza City, while another branch goes to Damascus, and to the cities of the Phoenician coast[10].

Language and script

We must first distinguish between a language and the script by which a certain language is written. Ancient South Arabians spoke their own language, which belongs to the Semitic language-groups (Akkadian, Hebrew, Arabic, Ethiopic). In 1841, two Germans scholars (Rödiger and Gesenius) succeeded in deciphering the Sabean language, and later, after about a century and a half, we have a wonderful dictionary of the Saba language.

Short vowels were neglected, if a Sabaean would write the word "Wine" it would be "WYN", the definite article was "n" suffix, so "the wine" would be "WYNN"; in fact, the word wine in the Sabaean langue was exactly "WYN", thus, Dr. Maraqten suppose that the Greek word oinos "stems from this Semitic word". It is worth noting that Ethiopic script (still used today) is derived directly of the south Arabia script, with the innovation of recording vowels.

Short vowels were neglected, if a Sabaean would write the word "Wine" it would be "WYN", the definite article was "n" suffix, so "the wine" would be "WYNN"; in fact, the word wine in the Sabaean langue was exactly "WYN", thus, Dr. Maraqten suppose that the Greek word oinos "stems from this Semitic word". It is worth noting that Ethiopic script (still used today) is derived directly of the south Arabia script, with the innovation of recording vowels.

Thousands of inscriptions varied in their length found around South Arabia land, this might be individuals' names, even broken shreds, or long royal monumental texts exceed a hundred lines. Specialists divide the Sabaean language into three main eras, according to script: the early, central, and late Sabaic. The oldest inscriptions found in South Arabian script on pottery goes back, at least, to the tenth century BC.

Ancient South Arabia has developed two genuine scripts: official monumental called Musnad, mostly documenting the performance of religious rites, the completion of construction work, or enacting laws, regulations, and prohibitions; the second script was popular script called Zabur.

The difference between them might be compared to lowercase & uppercase letters, in our modern days. Zabur was only discovered in the 1970s, it was used for private usage, while Musnad for official public and royal usage. Before Zabur was accidentally discovered, we had only hints about it in the Islamic sources. It is a minuscule script written on wood, contains private correspondings, financial records, purchase, agreements, spells, and dreams. A whole archive has been uncovered from the ancient city of Nashan, it is the largest private letters collection survived from the ancient world.

The difference between them might be compared to lowercase & uppercase letters, in our modern days. Zabur was only discovered in the 1970s, it was used for private usage, while Musnad for official public and royal usage. Before Zabur was accidentally discovered, we had only hints about it in the Islamic sources. It is a minuscule script written on wood, contains private correspondings, financial records, purchase, agreements, spells, and dreams. A whole archive has been uncovered from the ancient city of Nashan, it is the largest private letters collection survived from the ancient world.

Among the exciting discoveries is that we obtained a handful of pre-Islamic poems, which their grammatical and stylistic features do not share with any other known inscriptions, and can be considered as hymns or epic poems, praising the God Almaqah in his struggle against his enemies[11].

Each kingdom has its language, however, the Sabaean language remained dominant, and used in the inscriptions of other kingdoms, as a prestige language. Controversy, however, is going on the language actually spoken, but not necessarily written. scholars noticed a lot of words in the inscriptions, which had parallels in the dialects of modern Yemen. some inscriptions would not have been understood without comparing them to the modern dialects and the special terminology.

"The Himyaritic language described by medieval scholars and up to the substratum that has been preserved in the modem Arabie dialects of Yemen - fo1ming the latest stage in a continuous linguistic development that can be pursued for a span of almost 3000 years".[12]

Photo after: M. Jung 2021

Legacy and survivals

Yemen have enjoyed a remarkable continuity of ancient forms in language, customs and traditions. Ancient south Arabian survivals can be traced in our modern days through anthropological and ethnographical observations, since the ancient history is still occupying a significant role in the collective memory of the public. Some scholars argue that saint's cult is a continuation of ancient deities worshipping in the ancient religion; this includes annual collective visitation (pilgrimage) to the saint's tomb, in his birthday which coincides with a sacred time, mostly found in the southern and western parts of Yemen. A hunt to the ibex as a charm for obtaining rain, was still in use some decades ago in Hadhramaut[13] and resembles the ancient so called "ritual hunt".

Yemen have enjoyed a remarkable continuity of ancient forms in language, customs and traditions. Ancient south Arabian survivals can be traced in our modern days through anthropological and ethnographical observations, since the ancient history is still occupying a significant role in the collective memory of the public. Some scholars argue that saint's cult is a continuation of ancient deities worshipping in the ancient religion; this includes annual collective visitation (pilgrimage) to the saint's tomb, in his birthday which coincides with a sacred time, mostly found in the southern and western parts of Yemen. A hunt to the ibex as a charm for obtaining rain, was still in use some decades ago in Hadhramaut[13] and resembles the ancient so called "ritual hunt".

Serjeant and others view this organized Hunt as "a survival of the ancient religion, is still in existence" and thus opposed, as un-Islamic, by the Hadhrami ulema.[14] "are proud of their history, their culture, and their buildings, and they see no discontinuity between their pre-Islamic and their Islamic past"[15]

.

Scholars also see a relation between some Yemeni mosques and the Ka'ba in Mecca[16], and that "at least one of the typologies of Yemeni mosques dates directly back to the pre-Islamic temple architecture", and some take it that the development of the classical mosque actually rooted in South Arabia [17]. The popular religious believes and rituals in Yemen have always been subject to attack by orthodox Islamic groups as paganism and witch practices, or simply deception. Rainmaking rituals, vows offerings to holy men and sanctuaries or tombs, decorating the buildings with ibex horns as protection amulet, dreams inspiration[18], folk stories related to ancient historical figures, tithes payment organization[19], sacred enclaves' organization[20], and more, all are interesting phenomena of survivals in this land.

Scholars also see a relation between some Yemeni mosques and the Ka'ba in Mecca[16], and that "at least one of the typologies of Yemeni mosques dates directly back to the pre-Islamic temple architecture", and some take it that the development of the classical mosque actually rooted in South Arabia [17]. The popular religious believes and rituals in Yemen have always been subject to attack by orthodox Islamic groups as paganism and witch practices, or simply deception. Rainmaking rituals, vows offerings to holy men and sanctuaries or tombs, decorating the buildings with ibex horns as protection amulet, dreams inspiration[18], folk stories related to ancient historical figures, tithes payment organization[19], sacred enclaves' organization[20], and more, all are interesting phenomena of survivals in this land.

"Islamic writers speak conventionally in the idiom of innovators and heresies, as if there had in times past existed all over the country a completely islamized society. It is of course Islamic shari'ah that is innovatory in the territory"[21].

The decline of Yemeni civilization and the rapid extinction of the South Arabic language remains a mystery, as is the case for many aspects of this rich civilization, still we can hope, in a prospering Yemen, in that future excavations will reveal its fascinating history.

Further readings:

- Yemen: 3,000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix.

- Alessandro De Maigret (2002), Arabia Felix, Translated by Rebecca Thompson.

- Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde München, W. Daum, W. W. Müller, N. Nebes, W. Raunig (Hg.), Im Land der Königin von Saba. Kunstschätze aus dem antiken Jemen, München.

- Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies (since 1971). [scientific journal]

- Chroniques yéménites (حوليات يمانية), 2002, 2003, 2006, 2009, (in Arabic).

- JEMEN, Kunst und Archäologie im Land der Königin von Saba, Wien, Künstlerhaus, 9. November 1998 bis 21. Februar 1999, Wilfried Seipel (Illustrated Catalog)

- Montgomery Watt, W. (1947). "The Queen of Sheba in Islamic Tradition", in: James B. Pritchard (ed.), Solomon & Sheba, London: Phaidon, pp. 85-103.

- Yemeni Encyclopedia (الموسوعة اليمنية), 3 vols. (in Arabic).

Find more readings about Yemen here

Online projects:

Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions: http://dasi.cnr.it/index.php?id=26&prjId=1&corId=0&colId=0&navId=0

Sabaean-German dictionary: http://sabaweb.uni-jena.de/SabaWeb

Word Analysis for Ancient South Arabian Languages: http://www.ruzicka.net:8180/kalam/servlet/kalam

Resources:

[1] Walter W. Müller (). "Outline of the History of Ancient Southern Arabia", Yemen 3000, p. 49

[2] Mounir Arbach (2003), p. 11.

[3] Mounir Arbach (2006), p. 64.

[4] Christian Robin (2003), "Saba and the Sabaeans" (in Arabic) Chroniques Yéménites, the French Center for Archaeology and Social Sciences – Sana'a, p. 17.

[5] Ryckmans, J. (1988). "The old south Arabian religion" In: Yemen: 3,000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, 107-110. Innsbruck: Pinguin-Verlag, p. 107-108.

[6] Ryckmans, J. (1988). "The old south Arabian religion" In: Yemen: 3,000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, 107-110. Innsbruck: Pinguin-Verlag, p. 108.

[7] Maraqten, M. (2021). Temple/Maḥram Bilqīs, Ma'rib, Yemen. South Arabian Long-Distance Trade In Antiquity: “Out Of Arabia”, pp. 430-456.

[8] Ryckmans, J. (1988). *The old south Arabian religion* In: Yemen: 3,000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, 107-110. Innsbruck: Pinguin-Verlag, p. 110.

[9] Walter W. Müller (). *Outline of the History of Ancient Southern Arabia*, Yemen 3000, p. 49.

[10] Yemeni Encyclopedia, vol. 2, II, 589-601. [in Arabic]

[11] Maraqten, M. (2015). Sacred spaces in ancient Yemen—The Awām Temple, Maʾrib: A case study. Pre-islamic South Arabia and its neighbours, p. 111.

[12] Stein, P. (2008). The “Ḥimyaritic” Language in pre-Islamic Yemen. A Critical Re-evaluation, p. 211.

[13] Ryckmans, J. (1988). "The old south Arabian religion" In: Yemen: 3,000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, 107-110. Innsbruck: Pinguin-Verlag, p. 110.

[14] Serjeant, R. B. (1976). South Arabian Hunt. Luzac. pp. 4, 84.

[15] Finster, B. (1992). An outline of the history of Islamic religious architecture in Yemen. Muqarnas, 9, p. 124.

[16] Finster, B. (1991). Cubical Yemeni Mosques. In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies (pp. 49-68). Seminar for Arabian Studies, p. 56; Finster, B. (1992), p. 125-126.

[17] Jung, M. (2021). A brief note on South Arabian spolia in Yemeni mosques. in: Sabina Antonini de Maigret & Alessio Agostini (eds.) Missione Archeologica Italiana in Yemen. Perugia, pp. 204, 203.

[18] ʿAṭbūš, M. A. (2021) “Ṭaqs al-nawm fī almaʿbad li-istijlāb al-waḥī - al-Ḥālūmah fī al-yaman al-qadīm”, Majallat dirāsāt tārīḫiyyah, Aden: Marakaz ʿadan li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-buḥūṯ at-tārīḫyyah wa-n-našr (7), pp. 5-41.

[19] Daum, W. (2017). Tithes for the God and the Origins of the Cult at Mecca-Continuity of Religious Practice in Arabia from the Pre-Islamic Period to the Present Day. Anthropos, 112(2), 517-536.

[20] Serjeant, R. B. (1962). Ḥaram and Ḥawṭah, the sacred enclave in Arabia. Mélanges Taha Husain, Le Caire, 1962, 41-58.

[21] Serjeant, R. B. (1993). Zinā, some forms of marriage and allied topics in Western Arabia. pp. 145, 156. [بتصرف].